I have a skittish relationship with naming my creator-self. Saying I’m an Artist, Artisan, Craftsperson, Ceramicist, or even just the tony nom-du-jour of Maker, bothers me sufficiently that shortly after I adopt one I find it uncomfortably limiting, if not damaging. While each may work as a signifier in the moment, they speedily run smack into the twin problems of demarcations and assumptions which divert, subvert, and pervert. The root problem I have with labels is sort of a chicken/egg connotative conundrum. Does the Maker’s making (as a pure process) inform the Made’s meaning? Or…does the Made Thing (a physical product) make the Maker something (as a byproduct of the product?) Humor me while I iron this out.

I’m thinking about all the making I did as a kid. It just fell out of me, really, with neither hindrance nor cheerleading from others. Some kids move their large muscles all day long, I just made stuff. My childhood was spent grooving on the possibilities for Girders and Panels Building Sets, making small worlds for my celluloid horses in the front yard shrubbery, putting Tab A into Slot A at every opportunity, or creating holiday choir boys from toilet paper roll tubes. I relished both winging it and following directions. The word “kit” still gives me a frisson, because a kit needs engagement from me! It comes down to a rampant curiosity about how the material world could be shaped – or misshaped. If one irons a wrinkled plastic dolly raincoat, one gets an iron-shaped hole; the Xacto knife can’t tell the difference between the oatmeal box and your thumb; if your bent-nail hammering splits the scrap wood ladder rung, it won’t hold your weight. And all other results from poking at the world with a kid-sized stick.

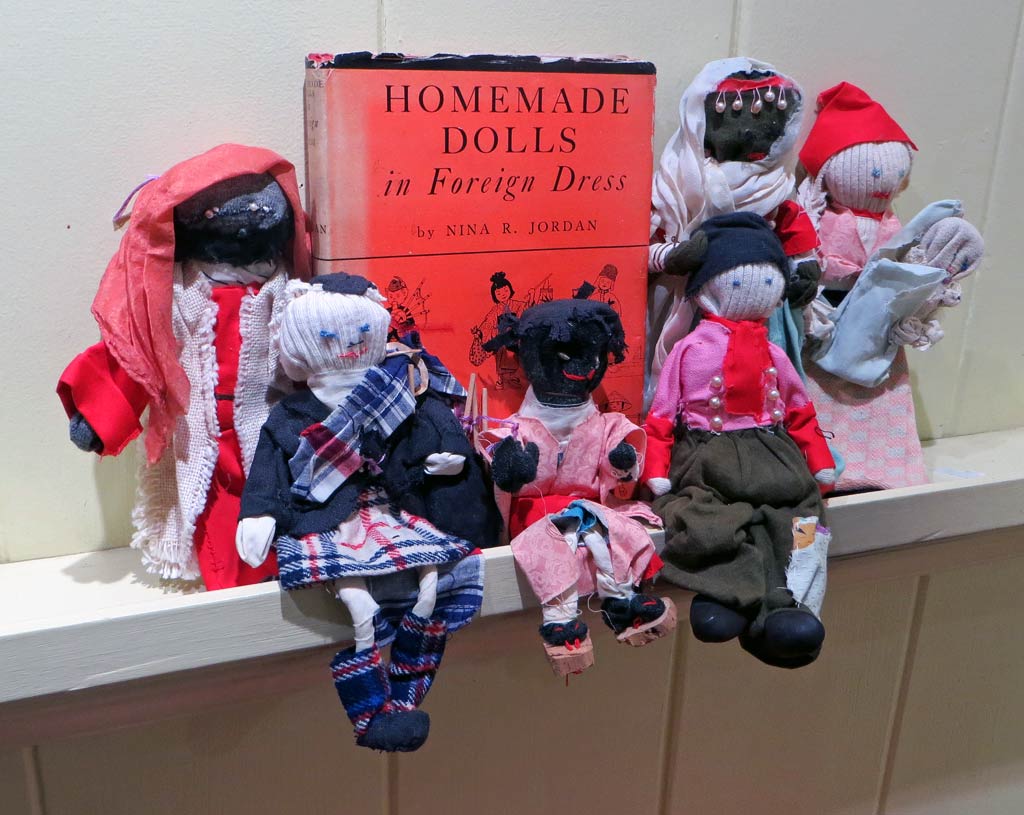

In probably my 11th summer I checked a book out of the library about multicultural dollmaking and made those dolls you see in the photo. As I recall, even though it wasn’t written especially for kids, the book took the reader by the hand with engaging cultural descriptions and habitats – houses, accessories, plants and animals – for each country’s doll. Its detailed patterns, methodology and material suggestions happily led to posable creations using wire armatures, old socks for padding and wrapping, and a whole lot of “materials for the taking” providing “happy uses for the scrap bag.”

I did not do this with a teacher, camp counselor or even a hovering parent; I just read the book and made the dolls I liked. I don’t recall showing them to anyone or playing with them, either. As far as I can tell, the fascination was purely with the resourceful god-like creating of a small human replica.

The book came due and summer ended. These dolls have lived in a lidded cedar box for five decades, through thirteen major moves and in countless storage spots. Whenever I brought them to light, as in down from the attic or in a closet clean-out, I marveled at their homely but honest detail and the patient skills of my preteen self. I wondered about that book, too. When I recently re-encountered them, I brought them out on display, which led to conversations and an internet vintage book search.

In the course of rediscovering these dolls made from youthful joy, along with the gift of finding that book, I am understanding my latest grown-up art-making from an unforeseen angle. My current clay+fiber explorations are so new to me, I don’t have words, labels or descriptions for them. And, unsurprisingly, considering the thought train I’m following here, I find I am rather loathe to develop any, fearing that my explanations won’t elucidate and expand, they will pidgeonhole and reduce both me and the work to mere nouns instead of verbs.

Which puts me smack in the Maker and the Made conundrum of meaning, too. To state it as simply as I can, it seems that making for making’s sake is a stand-alone experience, best kept away from of all the words and concepts, and I’d like to prolong that. Yet the act of making might be no more complex or meaningful than scratching an itch. A very human activity, but a closed loop. As lovely as the Utopia of Making is, one inevitably needs to step gingerly outside it and regard what one hath wrought. That’s an even more human activity! Once a Maker begins to assimilate the Made, the task to curate, explain, ascribe meanings and assign labels becomes a minefield and deserves assiduous authenticity. It is true that the transformations of physical materials in the act of creating both absorb and reflect on the Maker and the Made, but it’s the opposite of a closed loop. And it is true that unless words are adjusted, assumptions challenged, and meanings honed, the tendency will always be for labels and descriptions to become stale and inappropriate. Today’s meticulous manifesto is certain to sound off sooner than expected, might as well understand that at the outset and keep the explanations in line.

In his 1975 book, The Painted Word, Tom Wolfe grumpily observed that the world of fine art seemed to have devolved into an Explain First, Make Later proposition; that the critics wanted concepts more than they wanted works; that visual art had become literature. With manifestos, marketing and monetizing being household-level skills now, it’s tempting to metaphorically write in one’s artistic diary and then wishfully make to suit. Don’t. Ideas are legion and I’ve written before about art that is “merely clever,” a phrase I learned from my late mentor, Kathryn McBride – gone from this physical/material existence seven years now – who I would love to be sharing my nascent work with, getting her ever spot-on observations to feed my understanding of how it and I have changed and what to say about that.

Liz Crain – who loves that she, without having a glimmer of the title or author, could still find and buy for a few dollars a copy of the book that guided her to make these dolls. Within its cheerfully guileless but dated and unintentionally tone-deaf pages from 1939 was yet a lot of love for diversity, humankind and creating.

I can totally relate. I was a “maker” from age 4. My favorite things to make were clothes for my dolls and cardboard box houses (complete with furnishings and tiny dishes, clocks,etc) . My Barbies had Chanel worthy hand-knit suits and the Troll dolls had their own habitat in a bedroom corner. It is wonderful that you still have your dollies!

Hi Marlene! One of my three wishes as a kid was always to be able to get small enough to walk around in the dollhouse, wear the doll’s clothes and play with the doll things. I bet you did that too! Do you have photos of what you created and lived with that you can enjoy?

So great to know how you evolved- the dolls are amazing!!

Hi Jan! Yes, and thank you. I still wish I could remember more about making them, because I have so many questions about that in my creative dotage…